The transmission allows the gear ratio between the engine and the drive wheels to change as the car speeds up and slows down. You shift gears so the engine can stay below the redline and near the rpm band of its best performance. That is the idea behind the continuously variable transmission (CVT).

The transmission allows the gear ratio between the engine and the drive wheels to change as the car speeds up and slows down. You shift gears so the engine can stay below the redline and near the rpm band of its best performance. That is the idea behind the continuously variable transmission (CVT).

A transmission is a machine in a power transmission system, which provides controlled application of the power. Often the term transmission refers simply to the gearbox that uses gears and gear trains to provide speed and torque conversions from a rotating power source to another device.

In British English, the term transmission refers to the whole drivetrain, including clutch, gearbox, prop shaft (for rear-wheel drive), differential, and final drive shafts. In American English, however, the term refers more specifically to the gearbox alone, and detailed usage differs.

The most common use is in motor vehicles, where the transmission adapts the output of the internal combustion engine to the drive wheels. Such engines need to operate at a relatively high rotational speed, which is inappropriate for starting, stopping, and slower travel. The transmission reduces the higher engine speed to the slower wheel speed, increasing torque in the process. Transmissions are also used on pedal bicycles, fixed machines, and where different rotational speeds and torques are adapted.

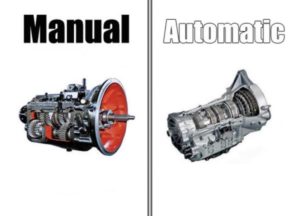

Often, a transmission has multiple gear ratios (or simply “gears”) with the ability to switch between them as speed varies. This switching may be done manually (by the operator) or automatically. Directional (forward and reverse) control may also be provided. Single-ratio transmissions also exist, which simply change the speed and torque (and sometimes direction) of motor output.

In motor vehicles, the transmission generally is connected to the engine crankshaft via a flywheel or clutch or fluid coupling, partly because internal combustion engines cannot run below a particular speed. The output of the transmission is transmitted via the driveshaft to one or more differentials, which drives the wheels. While a differential may also provide gear reduction, its primary purpose is to permit the wheels at either end of an axle to rotate at different speeds (essential to avoid wheel slippage on turns) as it changes the direction of rotation.

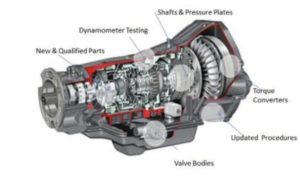

Conventional gear/belt transmissions are not the only mechanism for speed/torque adaptation. Alternative mechanisms include torque converters and power transformation (e.g. diesel-electric transmission and hydraulic drive system). Hybrid configurations also exist. Automatic transmissions use a valve body to shift gears using fluid pressures in response to speed and throttle input.

Explanation

Early transmissions included the right-angle drives and other gearing in windmills, horse-powered devices, and steam engines, in support of pumping, milling, and hoisting.

Most modern gearboxes are used to increase torque while reducing the speed of a prime mover output shaft (e.g. a motor crankshaft). This means that the output shaft of a gearbox rotates at a slower rate than the input shaft, and this reduction in speed produces a mechanical advantage, increasing torque. A gearbox can be set up to do the opposite and provide an increase in shaft speed with a reduction of torque. Some of the simplest gearboxes merely change the physical rotational direction of power transmission.

Many typical automobile transmissions include the ability to select one of several gear ratios. In this case, most of the gear ratios (often simply called “gears”) are used to slow down the output speed of the engine and increase torque. However, the highest gears may be “overdrive” types that increase the output speed.

Uses

Gearboxes have found use in a wide variety of different—often stationary—applications, such as wind turbines.

Transmissions are also used in agricultural, industrial, construction, mining and automotive equipment. In addition to ordinary transmission equipped with gears, such equipment makes extensive use of the hydrostatic drive and electrical adjustable-speed drives.

Simple

The simplest transmissions, often called gearboxes to reflect their simplicity (although complex systems are also called gearboxes in the vernacular), provide gear reduction (or, more rarely, an increase in speed), sometimes in conjunction with a right-angle change in direction of the shaft (typically in helicopters, see picture). These are often used on PTO-powered agricultural equipment, since the axial PTO shaft is at odds with the usual need for the driven shaft, which is either vertical (as with rotary mowers), or horizontally extending from one side of the implement to another (as with manure spreaders, flail mowers, and forage wagons). More complex equipment, such as silage choppers and snowblowers, have drives with outputs in more than one direction. So too Helicopters use a split-torque gearbox where power is taken from the engine in two directions for the different rotors.

The gearbox in a wind turbine converts the slow, high-torque rotation of the turbine into much faster rotation of the electrical generator. These are much larger and more complicated than the PTO gearboxes in farm equipment. They weigh several tons and typically contain three stages to achieve an overall gear ratio from 40:1 to over 100:1, depending on the size of the turbine. (For aerodynamic and structural reasons, larger turbines have to turn more slowly, but the generators all have to rotate at similar speeds of several thousand rpm.) The first stage of the gearbox is usually a planetary gear, for compactness, and to distribute the enormous torque of the turbine over more teeth of the low-speed shaft. Durability of these gearboxes has been a serious problem for a long time.

Regardless of where they are used, these simple transmissions all share an important feature: the gear ratio cannot be changed during use. It is fixed at the time the transmission is constructed.

For transmission types that overcome this issue, see Continuously variable transmission, also known as CVT.

Automotive basics

The need for a transmission in an automobile is a consequence of the characteristics of the internal combustion engine. Engines typically operate over a range of 600 to about 7000 rpm (though this varies, and is typically less for diesel engines), while the car’s wheels rotate between 0 rpm and around 1800 rpm.

Furthermore, the engine provides its highest torque and power outputs unevenly across the rev range resulting in a torque band and a power band. Often the greatest torque is required when the vehicle is moving from rest or traveling slowly, while maximum power is needed at high speed. Therefore, a system is required that transforms the engine’s output so that it can supply high torque at low speeds, but also operate at highway speeds with the motor still operating within its limits. Transmissions perform this transformation.

The dynamics of a car vary with speed: at low speeds, acceleration is limited by the inertia of vehicular gross mass; while at cruising or maximum speeds wind resistance is the dominant barrier.

Many transmissions and gears used in automotive and truck applications are contained in a cast iron case, though more frequently aluminium is used for lower weight especially in cars. There are usually three shafts: a mainshaft, a countershaft, and an idler shaft.

The mainshaft extends outside the case in both directions: the input shaft towards the engine, and the output shaft towards the rear axle (on rear wheel drive cars. Front wheel drives generally have the engine and transmission mounted transversely, the differential being part of the transmission assembly.) The shaft is suspended by the main bearings, and is split towards the input end. At the point of the split, a pilot bearing holds the shafts together. The gears and clutches ride on the mainshaft, the gears being free to turn relative to the mainshaft except when engaged by the clutches.

Manual

Manual transmissions come in two basic types:

Manual transmissions come in two basic types:

A simple but rugged sliding-mesh or unsynchronized/non-synchronous system, where straight-cut spur gear sets spin freely, and must be synchronized by the operator matching engine revs to road speed, to avoid noisy and damaging clashing of the gears

The now ubiquitous constant-mesh gearboxes, which can include non-synchronised, or synchronized/synchromesh systems, where typically diagonal cut helical (or sometimes either straight-cut, or double-helical) gear sets are constantly “meshed” together, and a dog clutch is used for changing gears. On synchromesh boxes, friction cones or “synchro-rings” are used in addition to the dog clutch to closely match the rotational speeds of the two sides of the (declutched) transmission before making a full mechanical engagement.

The former type was standard in many vintage cars (alongside e.g. epicyclic and multi-clutch systems) before the development of constant-mesh manuals and hydraulic-epicyclic automatics, older heavy-duty trucks, and can still be found in use in some agricultural equipment. The latter is the modern standard for on- and off-road transport manual and automated manual transmission, although it may be found in many forms; e.g., non-synchronised straight-cut in racetrack or super-heavy-duty applications, non-synchro helical in the majority of heavy trucks and motorcycles and in certain classic cars (e.g. the Fiat 500), and partly or fully synchronised helical in almost all modern manual-shift passenger cars and light trucks.

Manual transmissions are the most common type outside North America and Australia. They are cheaper, lighter, usually give better performance, but the newest automatic transmissions and CVTs give better fuel economy. It is customary for new drivers to learn, and be tested, on a car with a manual gear change. In Malaysia and Denmark all cars used for testing (and because of that, virtually all those used for instruction as well) have a manual transmission. In Japan, the Philippines, Germany, Poland, Italy, Israel, the Netherlands, Belgium, New Zealand, Austria, Bulgaria, the UK, Ireland, Sweden, Norway, Estonia, France, Spain, Switzerland, the Australian states of Victoria, Western Australia and Queensland, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania and the Czech Republic, a test pass using an automatic car does not entitle the driver to use a manual car on the public road; a test with a manual car is required.[citation needed] Manual transmissions are much more common than automatic transmissions in Asia, Africa, South America and Europe.

Manual transmissions can include both synchronized and unsynchronized gearing. For example, reverse gear is usually unsynchronised, as the driver is only expected to engage it when the vehicle is at a standstill. Many older (up to 1970s) cars also lacked synchronisation on first gear (for various reasons—cost, typically “shorter” overall gearing, engines typically having more low-end torque, the extreme wear on a frequently used first gear synchroniser), meaning it also could only be used for moving away from a stop unless the driver became adept at double-declutching and had a particular need to regularly downshift into the lowest gear.

Some manual transmissions have an extremely low ratio for first gear, called a creeper gear or granny gear. Such gears are usually not synchronized. This feature is common on pick-up trucks tailored to trailer-towing, farming, or construction-site work. During normal on-road use, the truck is usually driven without using the creeper gear at all, and second gear is used from a standing start. Some off-road vehicles, most particularly the Willys Jeep and its descendants, also had transmissions with “granny first’s” either as standard or an option, but this function is now more often provided for by a low-range transfer gearbox attached to a normal fully synchronized transmission.

Non-synchronous

Some commercial applications use non-synchronized manual transmissions that require a skilled operator. Depending on the country, many local, regional, and national laws govern operation of these types of vehicles (see Commercial Driver’s License). This class may include commercial, military, agricultural, or engineering vehicles. Some of these may use combinations of types for multi-purpose functions. An example is a power take-off (PTO) gear. The non-synchronous transmission type requires an understanding of gear range, torque, engine power, and multi-functional clutch and shifter functions. Also see Double-clutching, and Clutch-brake sections of the main article. Float shifting is the process of shifting gears without using the clutch.

Automatic

Most modern North American, and some European and Japanese cars have an automatic transmission that selects an appropriate gear ratio without any operator intervention. They primarily use hydraulics to select gears, depending on pressure exerted by fluid within the transmission assembly. Rather than using a clutch to engage the transmission, a fluid flywheel, or torque converter is placed in between the engine and transmission. It is possible for the driver to control the number of gears in use or select reverse, though precise control of which gear is in use may or may not be possible.

Most modern North American, and some European and Japanese cars have an automatic transmission that selects an appropriate gear ratio without any operator intervention. They primarily use hydraulics to select gears, depending on pressure exerted by fluid within the transmission assembly. Rather than using a clutch to engage the transmission, a fluid flywheel, or torque converter is placed in between the engine and transmission. It is possible for the driver to control the number of gears in use or select reverse, though precise control of which gear is in use may or may not be possible.

Automatic transmissions are easy to use. However, in the past, some automatic transmissions of this type have had a number of problems; they were complex and expensive, sometimes had reliability problems (which sometimes caused more expenses in repair), have often been less fuel-efficient than their manual counterparts (due to “slippage” in the torque converter), and their shift time was slower than a manual making them uncompetitive for racing. With the advancement of modern automatic transmissions, this has changed.

Attempts to improve fuel efficiency of automatic transmissions include the use of torque converters that lock up beyond a certain speed or in higher gear ratios, eliminating power loss, and overdrive gears that automatically actuate above certain speeds. In older transmissions, both technologies could be intrusive, when conditions are such that they repeatedly cut in and out as speed and such load factors as grade or wind vary slightly. Current computerized transmissions possess complex programming that both maximizes fuel efficiency and eliminates intrusiveness. This is due mainly to electronic rather than mechanical advances, though improvements in CVT technology and the use of automatic clutches have also helped. A few cars, including the 2013 Subaru Impreza and the 2012 model of the Honda Jazz sold in the UK, actually claim marginally better fuel consumption for the CVT version than the manual version.

For certain applications, the slippage inherent in automatic transmissions can be advantageous. For instance, in drag racing, the automatic transmission allows the car to stop with the engine at a high rpm (the “stall speed”) to allow for a very quick launch when the brakes are released. In fact, a common modification is to increase the stall speed of the transmission. This is even more advantageous for turbocharged engines, where the turbocharger must be kept spinning at high rpm by a large flow of exhaust to maintain the boost pressure and eliminate the turbo lag that occurs when the throttle suddenly opens on an idling engine.

Automated manual

A hybrid form of transmission where an integrated control system handles manipulation of the clutch automatically, but the driver can still—and may be required to—take manual control of gear selection. This is sometimes erroneously called “clutchless manual”, or “semi-automatic” transmission. It can simply and best be described as a standard manual transmission, with an automated clutch, and automated clutch and gear shift control. Many of these transmissions allow the driver to fully delegate gear shifting choice to the control system, which then effectively acts as if it was a regular automatic transmission. They are generally designed using manual transmission “internals”, and when used in passenger cars, have synchromesh operated helical constant mesh gear sets.

Early automated manual systems used a variety of mechanical and hydraulic systems—including centrifugal clutches, torque converters, electro-mechanical (and even electrostatic) and servo/solenoid controlled clutches—and control schemes—automatic declutching when moving the gearstick, pre-selector controls, centrifugal clutches with drum-sequential shift requiring the driver to lift the throttle for a successful shift, etc.—and some were little more than regular lock-up torque converter automatics with manual gear selection.

Most modern implementations, however, are standard or slightly modified manual transmissions (and very occasionally modified automatics—even including a few cases of CVTs with “fake” fixed gear ratios), with servo-controlled clutching and shifting under command of the central engine computer. These are intended as a combined replacement option both for more expensive and less efficient “normal” automatic systems, and for drivers who prefer manual shift but are no longer able to operate a clutch, and users are encouraged to leave the shift lever in fully automatic “drive” most of the time, only engaging manual-sequential mode for sporty driving or when otherwise strictly necessary.

A dual-clutch transmission alternately uses two sets of internals, each with its own clutch, so that a “gear change” actually only consists of one clutch engaging as the other disengages—providing a supposedly “seamless” shift with no break in (or jarring reuptake of) power transmission. Each clutch’s attached shaft carries half of the total input gear complement (with a shared output shaft), including synchronized dog clutch systems that pre-select which of its set of ratios is most likely needed at the next shift, under command of a computerized control system. Specific types of this transmission include: Direct-Shift Gearbox.

There are also sequential transmissions that use the rotation of a drum to switch gears, much like those of a typical fully manual motorcycle.[12] These can be designed with a manual or automatic clutch system, and may be found both in automobiles (particularly track and rally racing cars), motorcycles (typically light “step-thru” type city utility bikes, e.g., the Honda Super Cub) and quad bikes (often with a separately engaged reversing gear), the latter two normally using a scooter-style centrifugal clutch.

Uncommon Types

Dual Clutch Transmission

Dual Clutch Transmission

This arrangement is also sometimes known as a direct shift gearbox or powershift gearbox. It seeks to combine the advantages of a conventional manual shift with the qualities of a modern automatic transmission by providing different clutches for odd and even speed selector gears. When changing gear, the engine torque is transferred from one gear to the other continuously, so providing gentle, smooth gear changes without either losing power or jerking the vehicle. Gear selection may be manual, automatic (depending on throttle/speed sensors), or a ‘sports’ version combining both options.

Continuously Variable

The continuously variable transmission (CVT) is a transmission in which the ratio of the rotational speeds of two shafts, as the input shaft and output shaft of a vehicle or other machine, can be varied continuously within a given range, providing an infinite number of possible ratios. The CVT allows the driver or a computer to select the relationship between the speed of the engine and the speed of the wheels within a continuous range. This can provide even better fuel economy if the engine constantly runs at a single speed. The transmission is, in theory, capable of a better user experience, without the rise and fall in speed of an engine, and the jerk felt when changing gears poorly.

CVTs are increasingly found on small cars, and especially high-gas-mileage or hybrid vehicles. On these platforms, the torque is limited because the electric motor can provide torque without changing the speed of the engine. By leaving the engine running at the rate that generates the best gas mileage for the given operating conditions, overall mileage can be improved over a system with a smaller number of fixed gears, where the system may be operating at peak efficiency only for a small range of speeds. CVTs are also found in agricultural equipment; due to the high-torque nature of these vehicles, mechanical gears are integrated to provide tractive force at high speeds. The system is similar to that of a hydrostatic gearbox, and at ‘inching speeds’ relies entirely on hydrostatic drive. German tractor manufacturer Fendt pioneered the technology, developing its ‘Vario [1]’ transmission.

Infinitely Variable

The IVT is a specific type of CVT that includes not only an infinite number of gear ratios, but an “infinite” range as well. This is a turn of phrase, it actually refers to CVTs that are able to include a “zero ratio”, where the input shaft can turn without any motion of the output shaft while remaining in gear. The gear ratio in that case is not “infinite” but is instead “undefined”.

Most (if not all) IVTs result from the combination of a CVT with an epicyclic gear system with a fixed ratio. The combination of the fixed ratio of the epicyclic gear with a specific matching ratio in the CVT side results in zero output. For instance, consider a transmission with an epicyclic gear set to 1:−1 gear ratio; a 1:1 reverse gear. When the CVT side is set to 1:1 the two ratios add up to zero output. The IVT is always engaged, even during its zero output. When the CVT is set to higher values it operates conventionally, with increasing forward ratios.

In practice, the epicyclic gear may be set to the lowest possible ratio of the CVT, if reversing is not needed or is handled through other means. Reversing can be incorporated by setting the epicyclic gear ratio somewhat higher than the lowest ratio of the CVT, providing a range of reverse ratios.

Electric Variable

The Electric Variable Transmission (EVT) combines a transmission with an electric motor to provide the illusion of a single CVT. In the common implementation, a gasoline engine is connected to a traditional transmission, which is in turn connected to an epicyclic gear system’s planet carrier. An electric motor/generator is connected to the central “sun” gear, which is normally un-driven in typical epicyclic systems. Both sources of power can be fed into the transmission’s output at the same time, splitting power between them. In common examples, between one-quarter and half of the engine’s power can be fed into the sun gear. Depending on the implementation, the transmission in front of the epicyclic system may be greatly simplified, or eliminated completely. EVTs are capable of continuously modulating output/input speed ratios like mechanical CVTs, but offer the distinct benefit of being able to also apply power from two different sources to one output, as well as potentially reducing overall complexity dramatically.

In typical implementations, the gear ratio of the transmission and epicyclic system are set to the ratio of the common driving conditions, say highway speed for a car, or city speeds for a bus. When the driver presses on the gas, the associated electronics interpret the pedal position and immediately set the gasoline engine to the RPM that provides the best gas mileage for that setting. As the gear ratio is normally set far from the maximum torque point, this set-up would normally result in very poor acceleration. Unlike gasoline engines, electric motors offer efficient torque across a wide selection of RPM, and are especially effective at low settings where the gasoline engine is inefficient. By varying the electrical load or supply on the motor attached to the sun gear, additional torque can be provided to make up for the low torque output from the engine. As the vehicle accelerates, the power to the motor is reduced and eventually ended, providing the illusion of a CVT.

The canonical example of the EVT is Toyota’s Hybrid Synergy Drive. This implementation has no conventional transmission, and the sun gear always receives 28% of the torque from the engine. This power can be used to operate any electrical loads in the vehicle, recharging the batteries, powering the entertainment system, or running the air conditioning system. Any residual power is then fed back into a second motor that powers the output of the drivetrain directly. At highway speeds this additional generator/motor pathway is less efficient than simply powering the wheels directly. However, during acceleration, the electrical path is much more efficient than an engine operating so far from its torque point.[17] GM uses a similar system in the Allison Bus hybrid powertrains and the Tahoe and Yukon pick-up trucks, but these use a two-speed transmission in front of the epicyclic system, and the sun gear receives close to half the total power.

Car Repair of Lawrenceburg, KY

859-285-9661

Credit/Link: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transmission_(mechanics)